SF 88 and the Cuban Missile Crisis

Cloud from 1st nuclear explosion, “Mike.”

I was scouting sites in San Francisco for a new novel. I called my old friend Dan. He’s been doing audio for films for decades, starting with Apocalypse Now. I figured he’d seen some strange locations.

I asked him, “What have you got that’s really creepy?”

He thought a moment, then said, “I once recorded sound effects in this abandoned nuclear missile silo somewhere up in the Marin Headlands. You have to imagine this dark, empty cavernous space, water drops echoing off concrete walls….”

I was imagining it. “Let’s go.”

“Oh, I doubt we can get in. The film people must have pulled some strings – I don’t remember. But you don’t just walk into a place like that.”

“Let’s try.”

We pulled down a steep bend in the road, past some old barracks, and up to a gate guarded by these guys:

A sign. “Visiting hours – 3-5 Wed-Fri.”

3:30 on a Thursday. We were in luck.

It turned out we’d stumbled onto the only Nike -Hercules missile site in the country that’s open to the public. It was recently refurbished, all set for launch. Except for the warheads. Thank God.

A young fellow in a National Park uniform strode up and asked, “You want to take the tour?”

“You bet.”

He pointed to the radar that had guided the missiles:

Then he cut to the chase. He ushered us into an unassuming shed, and there it was: a nuclear missile.

My curiosity was already aroused. Now I felt an odd excitement.

The guide said, “We’ll start with this clip from a movie from back then, explaining these launch sites.” A blast of trombones, and one of those stentorian announcers. But I wasn’t watching. I was remembering.

Fifth grade. A piercing alarm waking me from my usual daydreaming. We leapt from our desks and ran to the hall, our teacher yelling, “Don’t run.” Don’t run, it’s only a nuclear war. Along with the others, I opened my locker and stuck my head in, as I’d been instructed.

I waited through long minutes, sweating in the silence, for the all clear…. or for that other possibility, I snuck a look out the side of my eye to the large plate glass window next to the door. I waited for that flash of light, brighter than the sun, for the glass to implode, for my eyeballs to melt down my face like I’d read in the book Hiroshima.

And I thought – how stupid can they be, to think these flimsy lockers are going to do any good against that?

The video screen showed “The End” and I came back to the present. What I couldn’t understand was that as I sat there, blind to the film, remembering, I wasn’t feeling that old dread. In fact, I was still excited. Why?

The guide said, “When it came time to launch they cranked them up to about 89 degrees. Not vertical. Otherwise they’d come right back down on their heads.” He looked up. We all laughed nervously.

He pointed to this:

Sign next to it said, “First computer.” I wondered if Steve Jobs had ever seen it.

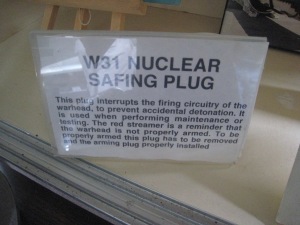

He showed us this safety plug:

“The missile didn’t work until you removed it.”

After which, it did work.

I guess if something went wrong you could wear one of these:

We walked outside, towards the launch area.

My dad, like all good liberals at the college, scoffed at bomb shelters. He said, “There’s a guy down the street who dug one in his backyard. He has a shotgun to keep his neighbors out,” as if that explained the preposterousness of bomb shelters.

But I didn’t care about preposterous. I cared about living. I went in the little room in the back of the basement and started smuggling cans of tuna down from the kitchen to make my own bomb shelter. Was it deep enough underground? It was better than those lockers.

I felt like these memories belonged to someone else. Like I’d never lived that terror. Because I just wasn’t feeling it.

We saw the door the missile hid under:

The guide brought a missile up from the silo below on an elevator.

We rode down into the silo with him, holding onto the cold side of it so we wouldn’t fall in the pit. My excitement grew. He explained how during a few tense times the operators had slept down in this concrete hole with the missiles. He led us through a maze of narrow corridors, past three six-inch solid steel doors into the bunker.

Without those doors the operators would be incinerated by the blast of the launch. I pointed to a red button on the moldering console. “That’s the one, isn’t it?” I was smiling.

“Yep.”

I asked the guide his age.

“24.”

“So of course you don’t remember the Cuban Missile Crisis.”

“I’ve heard about it.” He said it without a hint of feeling, like I’d said, “Of course you don’t remember the Battle of Hastings.”

We stood in the silo, the guide explaining the actual sequence of launch. I missed most of it, because now I was remembering October, 1962.

They told us about the crisis at school. I came home to an empty house and turned on the TV.

Walter Cronkite pointed to a map with concentric circles around New York marking the affected regions of a Soviet nuclear attack, intoning in that unflappable voice just what would happen if you lived within this one, then that one. Living two hours from Manhattan, we should expect a few days of puking our guts out, then we’d all die.

When my father got home from work he stood there staring at the TV too. He didn’t sit down. I looked up to him for reassurance, but none was forthcoming. I asked, “What’s going to happen?” “I don’t know.” I could see the fear on his face.

That moment etched itself in my consciousness with the strength of sulfuric acid.

In that moment my doubts about the efficacy of lockers against blast crystallized into the realization that grownups didn’t know a thing about the stuff that really mattered.

I was starting to feel really guilty. Because I was still excited. And that unforgettable part of my personal history had about the same charge for me as the Battle of Hastings. What was going on?

The guide pointed to the missiles. “See those colored bands? They indicate the strength of the bomb. 2, 10, and that blue one is 20 megatons. Twice the power of the bomb we dropped on Nagasaki.”

A few years after that terrible day of the Cuban Missle Crisis, I met some survivors of Hiroshima, women who’d been little girls when it happened, and had the scars to show it. They spoke not in anger at us Americans, but of Peace. This was another unforgettable moment. I’d been living in terror ever since October of 1962, when the bombs almost dropped. Tears streamed down my face at the injustice of how these innocent girls had suffered. At the same time I grabbed, for that word: Peace. In that moment I became a confirmed pacifist. And a few years after that, as soon as I heard of “Peace and Love” I signed up, dropped out, dropped acid, and accepted Jimi Hendrix as my personal savior.

Now, for a moment, I finally felt something other than excitement. Pity for all those who’d suffered at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“Let me tell you about the guard dogs. Unless you were their trainer, they would tear your throat right out. The soldiers were more afraid of them than they were of nuclear war.”

Dan and I drove away. I felt very confused.

I took me a while to sort through my feelings about that tour. How could I, a pacifist, see that site and be excited? How could I remember those terrifying years and feel nothing?

Then I got it. I remembered something else. There had been a time before “duck and cover,” before the Cuban Missile Crisis. A time when I’d thought missiles were very cool. That time had been obliterated from my memory by what followed. But seeing that base, all that funky early 60s technology, brought it right back.

Third grade. I didn’t know that the Soviets had just launched Sputnik, freaking out the US government. All I knew was that I had to go to school an hour earlier – which I hated. And that we were studying a lot more math and science. Including rocket science. Which I loved.

Mrs. Plaistead pointed at the chart at the front of the class, naming the missiles in order, from shortest to tallest. Nike, Thor, Atlas, Titan….

I was too young to get the awful phallic implications of those erected weapons – Mine’s bigger than yours!

Those missiles are just about the only thing I remember from twelve years of school. The only thing interesting enough to pay attention to.

Truth is, over the decades I’ve lost my fear of nuclear war. I don’t know why. Being an adult hasn’t made me trust the adults running things any more than I did then. Less, actually. Which is I think the reason. If those fuckups haven’t succeeded in starting a nuclear war in over fifty years, it looks like we’re in luck, and they just can’t do it.

All words and pics copyright 2012 by John Manchester, except for “Mike” (Public Domain.)

Views: 5

Comments

Hadn’t heard of the head-in-the-locker trick. We just hid under our desks. As I was to find out a few short years later, it wouldn’t have mattered a damn. Those not obliterated by the blast were on their own — there would be no rescue.

As for the missile crisis, I remember it, but not with any great emotional loading. I just didn’t give a damn. And I’ve never seen much of a difference between American missiles in Germany aimed at Moscow and Soviet missiles in Cuba aimed at Washington.

As for my own country, to paraphrase a former prime minister speaking to the UN, we’re the only ones capable of making a nuclear bomb that have chosen not to. I’m rather proud of that.

HUGGGGGGGGGG

“In that moment my doubts about the efficacy of lockers against blast crystallized into the realization that grownups didn’t know a thing about the stuff that really mattered.”

I think kids are at the point point of realizing adults don’t know much of anything at a a younger age these days. I’m not surprised at their behavior considering the ignorance of many of the role models around.

Insightful and fascinating piece, past to present, I wonder about the future. Sad to think of those women and the millions of others victims of past evils. I’m hopeful that you’re right about the current batch of fuck-ups in charge.

Putting your head in the locker? I’d think the boys would pass out from the fumes of their PE clothes long before they’d fall victim to nuclear fallout.

I hope you’re right about the fuck-ups.